One of the best articles I have seen this spring comes from the Harvard Business Review, entitled “It’s better to avoid a toxic employee than hire a superstar”. You can read it here.

Previously on this blog we’ve talked about toxic employees, the importance of engagement, and the value of high performers. It’s easy to get lost in each of these topics individually, but what HBR does well is capture the overlap of some of the factors involved.

Most notable from the article are:

- The cost of a toxic employee on other staff exceeds the revenue brought in by a superstar.

- Toxic employees tend to be productive and in many cases are high performers. They rarely fit the archetype we might have of a lazy underperformer being your biggest problem.

- Toxic employees have staying power in many cases because of their performance and because they often also have the attractive characteristics of charisma, curiosity, and high self-esteem.

For me the most resounding quote I saw was:

“Overconfident, self-centered, productive, and rule-following employees were more likely to be toxic workers. One standard deviation in skills confidence meant an approximately 15% greater chance of being fired for toxic behavior, while employees who were found to be more self-regarding (and less concerned about others’ needs) had a 22% greater likelihood. For workers who said that rules must always be followed, there was a 25% greater chance he or she would be terminated for actually breaking the rules. They also found that people exposed to other toxic workers on their teams had a 46% increased likelihood of similarly being fired for misconduct.”

So what does this mean in the world of fundraising? For one thing it helps to explain why so many programs have difficulty or reluctance in dealing with toxic employees – they outperform their peers in a world where performance is everything. What happens when we reward that behavior, however, is the pattern of toxic behavior spreads to other team members, in many cases towards high performers who are otherwise good citizens of the organization.

Looking at this study it also occurs to me that we may inadvertently be selecting potentially toxic fundraisers during hiring. Our industry has been building a narrative of traits to look for in fundraisers that has high overlap with the qualities HBR has found are in abundance in toxic employees. In previous posts we have discussed what to look for in hiring, identifying potential, and evaluating fundraisers. While that advice still stands, it ignores one key component that we should look for in order to avoid hiring the confident, productive, yet toxic fundraiser: authenticity. Later this month I will spend some time elaborating on this key concept: how to look for authenticity, how to create an organization that fosters it, and how to leverage it for fundraising success.

____________________________________________________________

A side note: Many of you may have noticed that the blog has been on hiatus for a few months. This was due to a career move of my own. I am now back up and running. Please continue to comment, send in topic requests, and participate in the discussion.

.jpg)

.jpg)

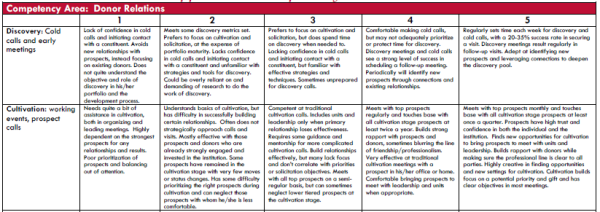

Additionally, organizations that don’t properly implement the use metrics to drive performance evaluation can create a disconnect between activity and strategic goals, causing managers to focus on tracking behavior over improving performance. According to BWF’s 2014 Survey of Frontline Fundraisers, approximately half of fundraisers believe that their metrics don’t reflect important activities. For those who have dual responsibilities (managing a volunteer program, leading a team, all while managing a portfolio, for example), there frequently are not concrete measurements for activities that make up sometimes over half of their workload. For others, uniform metrics do not adequately match the workload they face, depending on variance in the warmth of their portfolio, capacity of their prospects, or structural obstacles like leadership vacancies or lack of clarity on priorities that impede their performance.

Additionally, organizations that don’t properly implement the use metrics to drive performance evaluation can create a disconnect between activity and strategic goals, causing managers to focus on tracking behavior over improving performance. According to BWF’s 2014 Survey of Frontline Fundraisers, approximately half of fundraisers believe that their metrics don’t reflect important activities. For those who have dual responsibilities (managing a volunteer program, leading a team, all while managing a portfolio, for example), there frequently are not concrete measurements for activities that make up sometimes over half of their workload. For others, uniform metrics do not adequately match the workload they face, depending on variance in the warmth of their portfolio, capacity of their prospects, or structural obstacles like leadership vacancies or lack of clarity on priorities that impede their performance.