We’re watching many smaller organizations be innovative right now because they have no alternative; they’re fighting to survive. That innovation is coming from desperation, and it is draining intellectually and psychologically. For non-profit fundraising shops who are in serious, but not desperate shape we could choose to push for this type of innovation. We could make sure our employees are aware that there is an ax hanging over their heads and we may see some of our colleagues who step up (fight), some who resist any different practices (flight), and others who become paralyzed from doing new work or their old work (freeze). After all no one – not even professional athletes – does better under pressure. There is no such thing as a clutch player.

Innovation tends to come from one of two things: inspiration or desperation.

It is more difficult and requires stronger leadership to feel the pressure of the crisis we are in and choose to inspire innovation rather than hope the stress of the situation forces new practices. Below are some questions leaders should be asking themselves:

Am I making space for creativity?

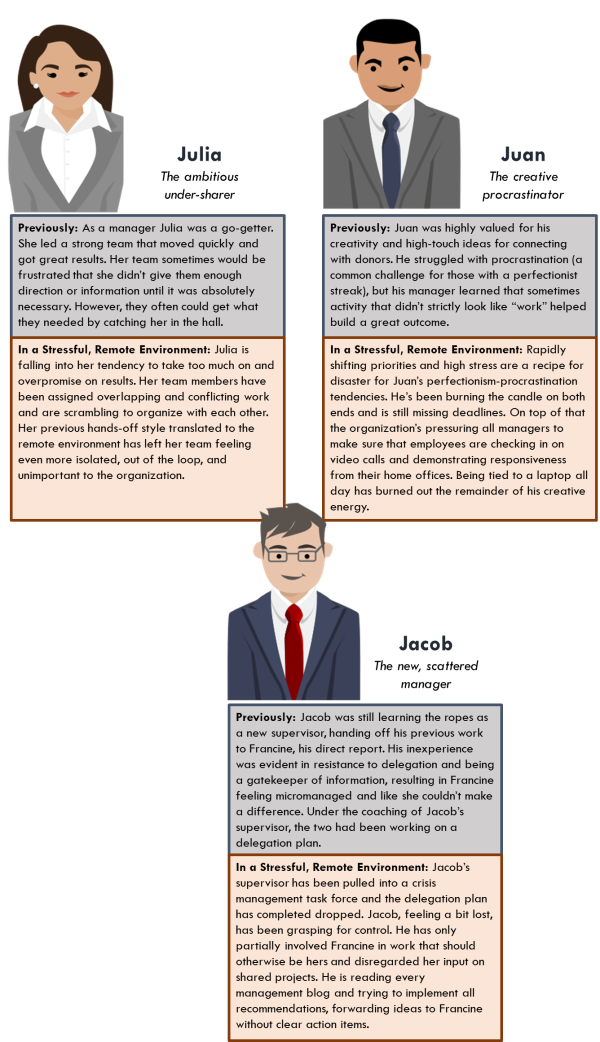

Even in an adjusted environment staff members tend to be wearing too many hats. In a normal situation development officers already struggle with spending enough time on frontline fundraising. They’re expected to be advisers, crisis communicators, administrators, managers, annual giving strategists, and high performing gift officers. If it’s difficult to be creative with a normally heavy workload, we cannot pile on new duties in crisis and expect big ideas to somehow emerge. Are leaders creating room and capacity within employees’ current roles or are they expecting them to simply add creativity to an already overloaded plate? Inspiration will not happen in the 5 minutes breaks between video calls and task list reviews.

What have I done to help inspire the team?

Connecting our teams to the mission of our organization is more critical now than ever. If we want our team members to think in new ways then we must help in inspiring them. Each individual employee might have a different motivator, which makes this difficult. A great leader making a speech to the entire team won’t inspire everyone – some may need more personal outreach, some may find inspiration in the direct stories of our organizations, and yet others may be inspired by being a resource for their colleagues. Leaders should be leveraging what they know about their teams and team members to build an ongoing strategy of outreach, inspiration, and connection.

Am I fostering psychological safety?

In a normal environment I would be writing an entire series about psychological safety in fundraising, but what leaders need to know right now is this: trust, vulnerability, and safety in failure drive innovation. Do we want fundraising staff to be taking risks right now? If the answer is no then we cannot expect innovation to happen. Leaders looking for increased creativity should be celebrating all good faith new efforts right now – even those that might fail. If a colleague is anticipating being penalized (socially, professionally or otherwise) for voicing a new idea, then they will never speak up. A note here: if employees didn’t feel psychologically safe prior to a crisis environment it will be nearly impossible to create that safety now.

Am I relinquishing control?

In high stress environments, performance drops when people put additional stress on themselves or feel heavily scrutinized. However, performance improves when those individuals feel that they have a level of influence or control in the situation. We cannot in the best of times control every aspect of our organizations, and asking individuals to wait for approval for every part of their job is demotivating and creates a strong barrier to creativity. Despite all instincts to bear down on what our staff members are doing (extra check ins, more meetings, increased tracking of activity) a leader’s time is better spent empowering their teams through defining duties, realms of influence, and project ownership.

No leader will be perfect right now. No employee is going to completely transform the world during COVID-19. That’s okay. By making sure we are motivating and empowering each other we will be able to come up with new ideas, try new things, and connect with our communities and donors in engaging ways.