Deloitte has released a new and very interesting report, Global Human Capital Trends. This report, which looks at trends across the for-profit and non-profit sector has some great data on the challenges faced by industries reliant on skilled, high-level human capital. In particular the report draws attention to the following:

Deloitte has released a new and very interesting report, Global Human Capital Trends. This report, which looks at trends across the for-profit and non-profit sector has some great data on the challenges faced by industries reliant on skilled, high-level human capital. In particular the report draws attention to the following:

This year’s 12 critical human capital trends are organized into three broad areas:

- Lead and develop: The need to broaden, deepen, and accelerate leadership development at all levels; build global workforce capabilities; re-energize corporate learning by putting employees in charge; and fix performance management

- Attract and engage: The need to develop innovative ways to attract, source, recruit, and access talent; drive passion and engagement in the workforce; use diversity and inclusion as a business strategy; and find ways to help the overwhelmed employee deal with the flood of information and distractions in the workplace

- Transform and reinvent: The need to create a global HR platform that is robust and flexible enough to adapt to local needs; reskill HR teams; take advantage of cloud-based HR technology; and implement HR data analytics to achieve business goals

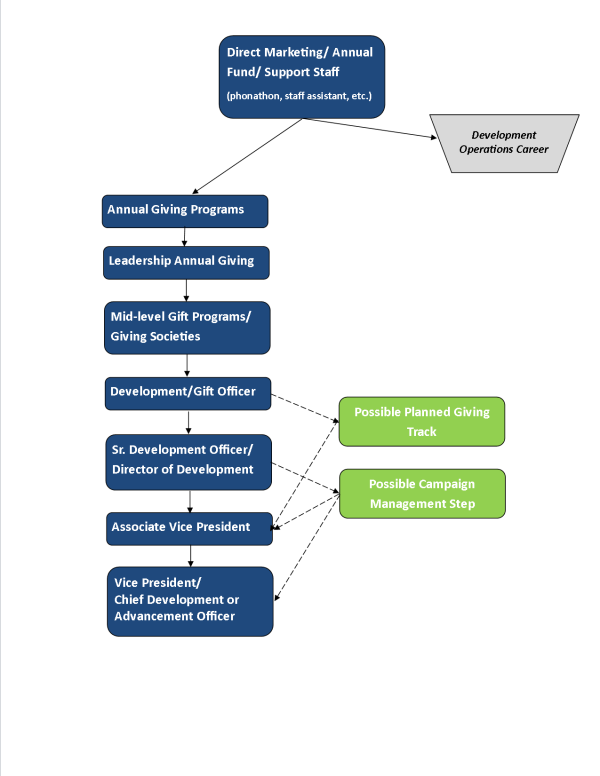

These three themes are especially applicable to strategic talent management in fundraising. We’ve discussed the importance and difficulty of leadership in development as well as the role of engagement in retention. The third element in the quote above reflects a rising consciousness in the development field. How we think about human resources globally needs to shift towards better strategy and comprehensive approaches.

Many development shops have only recently invested in owning their own team for hiring, overseeing, and training staff. Those that have succeeded have seen better results not only in the quality of their new hires, but in overall retention, engagement and satisfaction. Talent management needs to be more than conference attendance and a one-day orientation of new hires; it needs to be constantly adapting, assessing, and utilizing the engagement and skills of the team members of an organization. In fundraising we have many tools (metrics, analytics, professional seminars and conferences, database and portfolio management, etc). As development managers it is our responsibility to weild these tools meaningfully, while we apply some of the key traditional HR concepts described in this report.