Originally published February 26, 2015

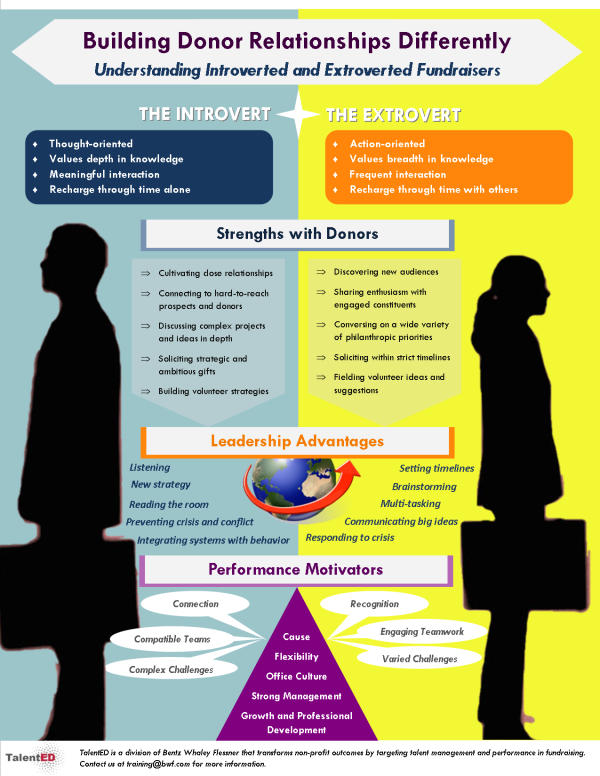

Fundraiser recruitment and retention is a hot topic in our industry for good reason: the demand for talented fundraisers far exceeds the supply. Development shops of all shapes and sizes are struggling to keep the talent they have. However, how we think about retention may be misguided.

There are a few key trends to consider:

- Most fundraisers believe that their salary and benefits packages are competitive.

- Less than 10% of front-line fundraisers are actively looking for a new job.

- Management and leadership largely shape how satisfied or dissatisfied team members are.

The trends listed above are about fundraisers in general, but there are several layers to how front-line fundraisers become engaged in your organization and vulnerable to poaching over time.

BWF studied how front-line fundraisers differed in their engagement based on their tenure at an organization. We found that retention strategies are better differentiated based on how long someone has been a member of the team, largely due to the following three trends:

Newcomers to the Team Need Time and Guidance to Adapt

Fundraisers with less than two years of tenure at an organization had slightly higher dissatisfaction rates and lower rates of high satisfaction than their peers who had been there at least two years(24% of those with <2 years reporting being very satisfied versus 36% of those who had been there 2–5 years). The top reason for dissatisfaction? Office culture. Regardless of whether newcomers to your development program are experienced professionals or novices, they are coming to an office with different values, relationships and approaches. Learning how to navigate a new institution and find your “fit” amongst a team is a top obstacle for new hires.

Team Members are Most Vulnerable to Poaching and Most Costly to be Poached Between Years 2 and 5

After the first two years, we can assume that newcomers who might have been frustrated with culture have either adapted or left. Fundraisers are then finding their stride, bonding with team members, progressing beyond a discovery-heavy portfolio, and seeing their first big successes with your donors. On average, their satisfaction increases. This is also the performance “ramp-up” period for fundraisers (our data show that portfolio performance grows slowly in newcomers through year 3 and then jumps dramatically). The institution begins to receive a healthy return on its investment during this period.

However, this is a period of high risk for losing your team members. Even though only 6% of this group is actively searching for a new position, nearly 30% are passively open to opportunities when they are approached. And after 24 months at an organization, fundraisers have a long enough time period on their resume to avoid raising eyebrows. Be assured that they are being contacted (27% report at least 10+ instances of contact about new opportunities in a year-long period). This can also be a period where team members become disillusioned, pointing to leadership and unrealistic expectations as primary causes of dissatisfaction.

Dissatisfaction Increases as Fundraisers Gain Tenure

Across stages of tenure, there is one more interesting trend: those with over a decade of experience at an institution have the highest dissatisfaction rates. High tenure fundraisers are more comfortable with your office culture and accustomed to the expectations placed upon them. They are, however, equally familiar with any dysfunction in your development office, particularly if there is weak management and leadership. Frontline fundraisers who have been at an institution over 10+ years may now have limited management oversight but bigger responsibilities and are more acutely affected by mismanagement than their lower tenure peers.

Source: Bentz Whaley Flessner Front-Line Fundraiser Study, 2014.

So What Does This Mean for You?

Here’s how you can hone your retention strategies based on these findings:

- Focus on easing the adjustment to a new culture and institution for new hires.

- Create growth and leadership opportunities before formal promotions.

- Improve transparency in expectations during fundraiser performance ramp-ups.

- Foster ownership of institutional and management improvements amongst high tenure team members.

BWF’s TalentED practice partners with non-profit institutions to optimize fundraising outcomes through customized team and skill-building workshops, talent management and learning development program assessments and planning, and thought leadership and research on the talent crisis in development. To learn more about how you might better find, keep, and grow your talent contact us at training@bwf.com.

Copyright © 2015 Bentz Whaley Flessner & Associates, Inc