In previous posts our TalentED team has emphasized the importance of practice and repetition in ensuring that fundraisers develop the skills and professional judgment necessary to achieve success as a major gift officer. I’m confident it’s now accepted wisdom that repetitive simulations and actual hands-on, in-the-moment interactions with donors are essential experiences in helping new gift officers master the art of fundraising—a process that includes discovery, cultivation, solicitation, negotiation and stewardship.

In previous posts our TalentED team has emphasized the importance of practice and repetition in ensuring that fundraisers develop the skills and professional judgment necessary to achieve success as a major gift officer. I’m confident it’s now accepted wisdom that repetitive simulations and actual hands-on, in-the-moment interactions with donors are essential experiences in helping new gift officers master the art of fundraising—a process that includes discovery, cultivation, solicitation, negotiation and stewardship.

As vitally important to performance as regular practice is, a recent article from Inc. Magazine reminded me that repetition alone cannot guarantee long-term fundraising success.

In “4 Short Lessons on How to Learn a New Skill,” author Sims Wythe posits that individuals who pursue mastery of a skill must also possess or receive four other factors if their repetition to yield meaningful improvement: (1) motivation, (2) knowledge, (3) application of knowledge, and (4) unequivocal feedback:

- Motivation

To get better at a skill, we must first want to improve. As Wythe states, “the first thing you have to do is simply begin…. And now that you know you want to begin, you have to be willing to fail, to be frustrated, to be bored, and to be angry that what looks so easy for some is so hard for you.” Without these internal or external incentives for improvement, we are unlikely to apply the necessary discipline, exert enough effort, or tolerate the impediments.

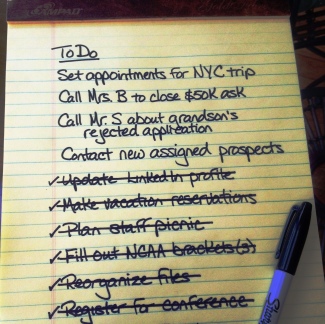

What motivates fundraisers to improve? At the very least, our supervisors expect and require us to become more polished and increasingly productive. Hopefully, we also bring to the task our own personal pride and desire for success. Nonetheless, even the very best fundraisers encounter obstacles, including objections and rejection by donors. It’s not an easy job—and these challenges certainly contribute to the rapid turnover among first-time major gift officers.

- Knowledge

For practice and repetition to make a difference, you have to be practicing the right things. As Wythe observes, if you practice your golf swing at the driving range every day of the summer but you have a lousy swing, it’s unlikely your swing will be any better on Labor Day. Wythe thus cites Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman, who advises that “…acquisition of skills requires a regular environment, an adequate opportunity to practice, and rapid and unequivocal feedback about the correctness of thoughts and actions.”

What does that mean for major gift officers? Your own ability to enhance your performance is limited. To get better, you need to observe effective fundraising in action, have access to resources that will inform you, and obtain feedback from other, more experienced fundraisers.

- Application of Knowledge

Practicing alone has limited value. You must also practice in front of others and in situations similar to those in which your actual performance will occur. For example, Wythe cites the process of becoming  a better public speaker: “the only proven way to become a better speaker is to rehearse under performance-like pressure…. It is hard to replicate real-life circumstances, but practicing your speech aloud to people who are familiar with your topic is—again—the only scientifically proven way of improving your speaking skills.”

a better public speaker: “the only proven way to become a better speaker is to rehearse under performance-like pressure…. It is hard to replicate real-life circumstances, but practicing your speech aloud to people who are familiar with your topic is—again—the only scientifically proven way of improving your speaking skills.”

For fundraisers, that means practicing the types of conversations that you must have with donors: getting the appointment, eliciting information, exploring interests, soliciting gifts, overcoming objections and making the close. As uncomfortable as it may be, live practice—and yes, even role playing—of donor conversations in front of other, more seasoned gift officers is critical to recognizing opportunities for improvement and identifying areas for further practice.

- Unequivocal Feedback

Once you begin performing the skills you’ve been developing and policing, it’s vital to evaluate your performance and to identify areas that require further practice and improvement. Indeed, Wythe suggests that we all need a coach; however we cannot be our own coaches: “You can read all the how-to books you want, but then you have to implement those suggestions—which takes a huge amount of discipline that most of us don’t have—and then you have to be able to see around your own blind spots which, believe me, will take a lifetime.”

have—and then you have to be able to see around your own blind spots which, believe me, will take a lifetime.”

Of course, few fundraisers have the resources to engage a personal coach. Instead, that role should be filled by your supervisor and your peers, and ideally, your organization will offer on-site training programs or opportunities to attend off-site workshops. But if your supervisor and peers don’t see themselves as coaches, or if you don’t have access to training programs, it is up to you to proactively seek out feedback and coaching: Ask your colleagues to provide the ‘rapid and unequivocal feedback’ Wythe says you need, or seek others to help fill that role. Just be sure that you enlist knowledgeable people who you trust to critique you without holding back.

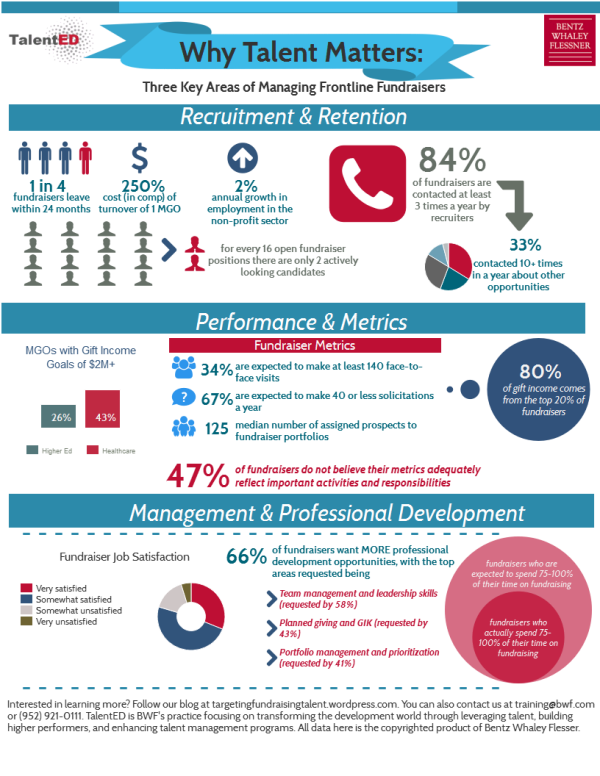

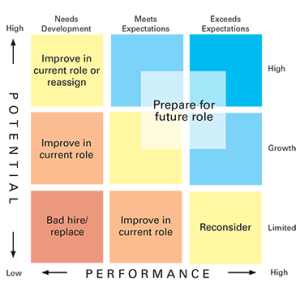

It should thus be good news for both new and seasoned fundraisers that the imperative for pursuing a comprehensive approach to building advancement teams is beginning to be acknowledged and to be addressed. By applying tenets of “strategic talent management” to the advancement profession, fundraising organizations are increasingly looking holistically at the entire process of finding, training, developing, rewarding and keeping the best possible gift officers. And training, coaching and mentoring are core elements of this fresh, holistic approach to growing talent. In addition, consulting and support organizations (such as Bentz Whaley Flessner and TalentED) are also ramping up their offerings to help clients develop talent management strategies, provide training and coaching, and better understand the dynamics of creating and maintaining effective fundraising teams.

It’s good news, for sure. But don’t stop practicing!

On this blog we’ve touched on some

On this blog we’ve touched on some

.jpg) Proactively focus on the people you want. The organizations that do best in fundraiser recruitment are proactive in hiring, not reactive. They look to a pool of previously identified candidates and desirable hires before a position is even open. Development shops should focus on who they would like to join the team in the next two years, not just what specific positions they would like to fill. Then, each open position becomes an opportunity to create the right appeal for the candidate you want.

Proactively focus on the people you want. The organizations that do best in fundraiser recruitment are proactive in hiring, not reactive. They look to a pool of previously identified candidates and desirable hires before a position is even open. Development shops should focus on who they would like to join the team in the next two years, not just what specific positions they would like to fill. Then, each open position becomes an opportunity to create the right appeal for the candidate you want..jpg) Be wary and know the signs of “position hoppers.” A recent BWF survey of fundraisers found that generally less than 7 percent are actively seeking new opportunities, while 25 percent are passively open to opportunities that are sent their way. Within this industry there is a subset of “position hoppers” who have resumes filled with 2- and 3-year stints at institutions with increasing title and prestige. Be very cautious with these candidates. Chances are your organization will not be the exception to their rule of taking the next bigger and brighter thing. Considering that true fundraiser performance doesn’t occur until around the 4th year, these sorts of hires are extremely risky for your organization, because in 24–36 months you will face yet another vacancy and a portfolio of partially developed prospects.

Be wary and know the signs of “position hoppers.” A recent BWF survey of fundraisers found that generally less than 7 percent are actively seeking new opportunities, while 25 percent are passively open to opportunities that are sent their way. Within this industry there is a subset of “position hoppers” who have resumes filled with 2- and 3-year stints at institutions with increasing title and prestige. Be very cautious with these candidates. Chances are your organization will not be the exception to their rule of taking the next bigger and brighter thing. Considering that true fundraiser performance doesn’t occur until around the 4th year, these sorts of hires are extremely risky for your organization, because in 24–36 months you will face yet another vacancy and a portfolio of partially developed prospects. Look for a history of strategy over activity. Many position descriptions for fundraisers request some history of soliciting gifts at a certain level. While a history of actual gifts secured can demonstrate competence and qualification, the candidate’s ability to use and create strategy to secure those gifts and to build the donor relationship is a more valuable predictor of success. There are fundraisers who technically have secured 7- and 8-figure gifts merely by having the luck of a particular prospect being assigned to their portfolio.

Look for a history of strategy over activity. Many position descriptions for fundraisers request some history of soliciting gifts at a certain level. While a history of actual gifts secured can demonstrate competence and qualification, the candidate’s ability to use and create strategy to secure those gifts and to build the donor relationship is a more valuable predictor of success. There are fundraisers who technically have secured 7- and 8-figure gifts merely by having the luck of a particular prospect being assigned to their portfolio.