Data is increasingly driving the world of development. The ability to access and utilize data has changed how teams are shaped, how donors are engaged, and where resources are allocated. In addition, development organizations and major gift teams have rapidly expanded, and new data tools allow real-time fundraiser activity reports to evaluate fundraiser performance.

Simply tracking metrics to evaluate performance, however, will not always predict or measure real performance by these team members. Focusing on one key performance indicator (KPI) can lead to ignoring other meaningful activities and successes. Organizations that don’t reflect on the meaning and strategy related to metrics can inadvertently encourage inefficiencies and non-productive actions in development officers’ quests to meet their annual goals.

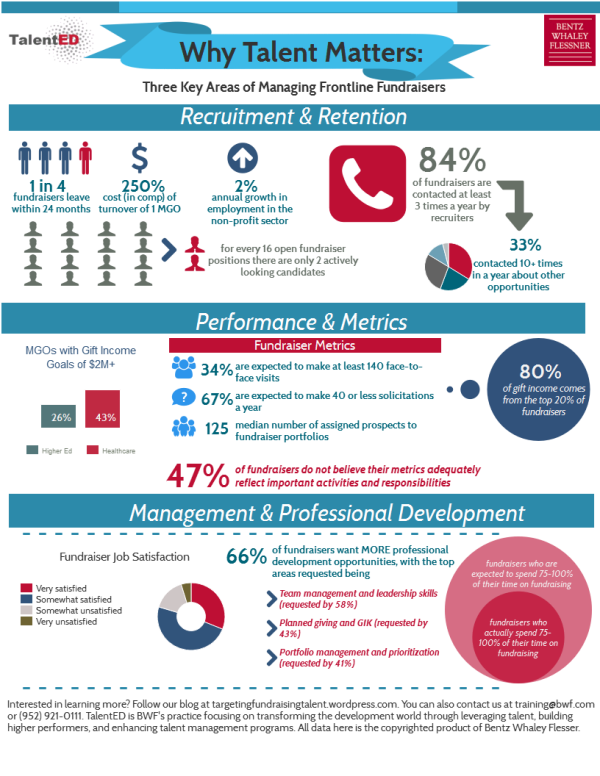

Additionally, organizations that don’t properly implement the use metrics to drive performance evaluation can create a disconnect between activity and strategic goals, causing managers to focus on tracking behavior over improving performance. According to BWF’s 2014 Survey of Frontline Fundraisers, approximately half of fundraisers believe that their metrics don’t reflect important activities. For those who have dual responsibilities (managing a volunteer program, leading a team, all while managing a portfolio, for example), there frequently are not concrete measurements for activities that make up sometimes over half of their workload. For others, uniform metrics do not adequately match the workload they face, depending on variance in the warmth of their portfolio, capacity of their prospects, or structural obstacles like leadership vacancies or lack of clarity on priorities that impede their performance.

Additionally, organizations that don’t properly implement the use metrics to drive performance evaluation can create a disconnect between activity and strategic goals, causing managers to focus on tracking behavior over improving performance. According to BWF’s 2014 Survey of Frontline Fundraisers, approximately half of fundraisers believe that their metrics don’t reflect important activities. For those who have dual responsibilities (managing a volunteer program, leading a team, all while managing a portfolio, for example), there frequently are not concrete measurements for activities that make up sometimes over half of their workload. For others, uniform metrics do not adequately match the workload they face, depending on variance in the warmth of their portfolio, capacity of their prospects, or structural obstacles like leadership vacancies or lack of clarity on priorities that impede their performance.

Unintended side effects of poorly implementing three of the most common metrics in the industry are highlighted below.

| Common Metric | Rationale | Unintentional Side Effect | |

| Number of Visits | Fundraiser performance is closely correlated with the amount of time he or she spends in the field and in front of donors. | Development officers meet with the same donors repeatedly and do not focus time on discovery or solicitation.The quality of the visit declines, and few strategic objectives are met during meetings with prospects. | |

| Number of Asks | Fundraisers should be expected to ask for gifts consistently and proactively. | Development officers ask too early in a relationship.Fundraisers ask for smaller than necessary gifts from high-capacity donors, seeking to get a gift on record over working for a long-term investment by the donor.

Cultivation activities are recorded as “asks” when a meaningful solicitation has yet to be made. |

|

| Total Gift Income Raised |

At the end of the year you look at what’s counted. Fundraisers’ primary responsibility is raising money. | High performers can be penalized for larger asks that are closed after the fiscal year.Low performers can be rewarded by large gifts that come in on their own but are assigned to their portfolio.

There is a desire to “own” as many prospects as possible. Credit sharing is misused to “tag into” large gifts, creating the impression of performance. |

The answer is not to abandon metrics altogether. Many of the challenges described above can be mitigated through proactive management by supervisors and accurate and thorough reporting on metrics. Measuring performance and especially facilitating feedback sessions with team members on the interpretation of those results is a critical component of talent management. Metrics need to therefore:

- Act as only one component of a larger system of understanding, creating accountability for, and evaluating performance.

- Take into account a development officer’s tenure and portfolio composition.

- Be created via collaboration between development officers and supervisors.

- Be implemented consistently and reported on frequently.

Discussions about areas for skill and knowledge growth and training needs should go hand in hand with this process. This way, professional development can be targeted towards and influence the right activities by development officers.

BWF’s TalentED practice provides customized training and workshop programs to help grow the capacity of development teams. For more information contact us at training@bwf.com.

Originally published May 14, 2015

Copyright © 2015 Bentz Whaley Flessner & Associates, Inc.