We live in the age of campaigns. Most non-profits right now are either:

| a. | In the middle of a major campaign. |

| b. | Closing out a large campaign. |

| c. | Planning for the next big campaign. |

| d. | Extending the timeline or raising the goal of a current campaign. |

Staffing goes hand-in-hand with preparing for and implementing a campaign. In development we expect to have to increase our staff sizes to increase fundraising results for a campaign. We spend a lot of time acknowledging the need to increase resources to increase results, but the process of “staffing up” can rapidly become convoluted. Below are four key questions that help steer us into the most effective campaign staffing situations.

How effective is our current team?

To create a campaign staffing plan, we have to take a hard look at who our current performers are and what our outcomes would be if we maintained the status quo. Part of this process is evaluating the fundraising team, both on existing performance and long-term potential. We have to take the time to make sure that our ratio of performers to non-performers is healthy and that team members are capable of handling the high expectations of a campaign. The tool below can help you map out the current strengths of your team.

.jpg)

How much time are our fundraisers currently spending on major giving?

When considering staffing for a campaign, leaders must ask this question first before choosing to simply add new fundraisers to the mix.

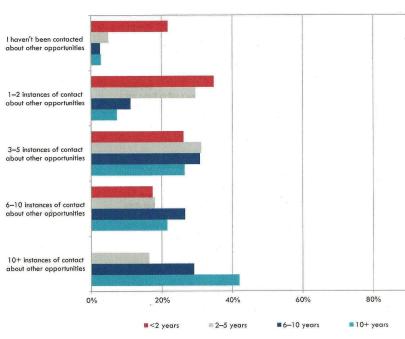

Through our talent management analysis and staffing assessments, BWF has consistently found that most fundraisers spend far less time on major giving than their job descriptions require. In many cases only half of fundraisers who are expected to spend 70% or more of their time on major giving are able to do so.

If your current frontline team members aren’t spending as much time as they could working on their portfolios and with their donors, then it would be wiser to invest in support and infrastructure. Consider this scenario:

If you have 100 fundraisers (average salary: $100K, average gift income: $1M) who have less than optimal time in the field: You can invest in 10 new fundraisers ($1M in salaries, $10M in post-ramp up gift income).

OR

You can strengthen targeted support areas and infrastructure to allow those fundraisers to spend even just 10% more time in the field (less than $500K in new salaries, $10M in gift income, immediate outcomes—no ramp-up delay).

Are there substantial obstacles or burdens on the team right now?

Bad policies or ineffective systems stall campaign momentum. Development leadership team members are responsible for ensuring that their frontline fundraisers are empowered to perform and execute during a campaign. When talking about staffing plans, therefore, the leadership team must identify and nullify any major barriers or obstacles that distract team members or prevent them from focusing on their top priorities. Typical barriers and obstacles are:

- Unclear goals or philanthropic priorities.

- Burdensome reporting or travel requirements.

- Inaccurate data or ineffective databases.

- Toxic organizational culture and/or personalities.

- Inefficient competition amongst teams over prospects, resources, or political power.

Can we count on retaining existing team members?

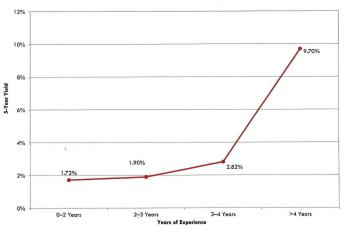

Results in a campaign often end up being driven by a select few high performers. As development leaders, we must ask ourselves if we know who those individuals are and if we have a strategy for retaining them. This is especially important considering that, for a frontline officer, it takes 3–4 years to begin to achieve high-level results. A staffing ramp-up means that any new hires are not likely to perform on the same level as their peers until several years into the campaign. If there is high staff turnover, then it doesn’t matter how large your organizational chart is: you will never fully realize the team’s potential or build meaningful momentum within your program. Retention can cost up to 250% of the open position’s salary in today’s hiring climate. Campaign staffing plans, therefore, must be about combating attrition as well as increasing overall FTEs.

BWF’s TalentED division focuses on the challenges, best practices, and strategy for talent management in development. To hear more about what we do or find answers to your own talent challenges contact us at training@bwf.com.

Copyright © 2015 Bentz Whaley Flessner & Associates, Inc.