I recently had the opportunity to interview Bruce Flessner, principal at Bentz Whaley Flessner. Bruce has been a lead consultant and adviser to top nonprofit development shops for over 30 years. I used my time with Bruce to focus on what his clients are saying about talent. The transcript of our conversation is below.

How often do your clients ask you about talent management?

Hourly. …

More seriously – it is something I get asked about every day. Not a day goes by that talent management doesn’t come up with my clients in one way or another. I have regular conversations with leaders who don’t have enough people, or they have the wrong people, or their people are doing the wrong things.

Do you see this problem more in any specific sector of the nonprofit world?

No. It’s widespread across all non-profit sector. From my experience it isn’t any better in any sector. Some areas might have stronger players as individuals because they are bigger; they’re raising more money and bringing in bigger gifts. But, what I have seen, is that even the largest shops have trouble with their talent, because those stronger players are more and more in demand.

What are some of the common challenges you see across the US in finding and keeping talent?

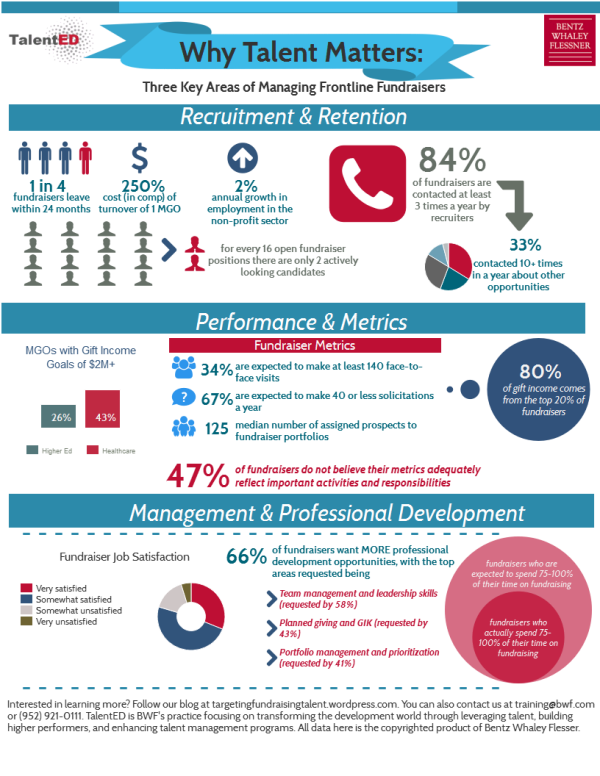

The first challenge I usually see is that there is more demand for new positions than there is supply of talent. We are constantly dealing with people expanding the size of their development programs and launching major campaigns and fundraising pushes. The number of non-profits is growing as is the size of development programs across the country. That growth has been hard to support with experienced fundraisers.

As a result I see the second trend of how hard it is for these shops to retain their stars because they’re in constant demand to staff and lead these campaigns and big initiatives anywhere. A good fundraiser is constantly going to be on the receiving end of recruitment and job offers, which makes retention very difficult.

The third challenge I see is that development programs, realizing they have to grow more talent to meet demand, face a conundrum. Leaders within a program are caught between needing to going out and do the fundraising work itself with donors and volunteers and committing time internally to train and develop new people. This tends to spread your best people thin.

What have you seen institutions do to successfully recruit and retain talent?

Some of the largest institutions have been able to develop in-house talent management offices and programs. I’ve seen that strategy succeed in improving recruiting efficiency and supporting training initiatives. However, it hasn’t solved all problems as often talent management individuals might not be as well versed in development and can miss areas of professional development or opportunities to find new hires.

I’ve seen others reach out to third parties to find new training opportunities for young staff, but the programs that are out there tend to be hit or miss. Often times you see a program try to host or send it’s fundraisers to a training, but it has no real outcome because the content and skills-work hasn’t been coordinated with the direction of the program or needs of the group.

What would you advise a non-profit looking towards a hiring push in fundraising or big growth in their development program?

- You need to be able to develop your own talent. You’re not going to be ina position where you can always go out and buy talent, even if you have the budget to do so. Competition is too stiff.

- Make talent management a serious part of how you evaluate and use senior leadership. Your leaders’ performance evaluations should touch on how commited and effective they are at developing junior people as well as growing the overally abilities and capacity of their teams.

- It is easy to spend a lot of your time on recruitment, but you probably should spend more time ensuring that you can keep your existing most accomplished individuals, because others are spending their time seeing if they can snatch your best performers. Without planning and programs for retention you can get in a cycle of losing your best people every few years. A lost experienced fundraiser becomes a lot more expensive than a new hire.

Let’s turn to the perspective of those who might be the candidates for these many open positions. What do you think those top performers are looking for in their current and potential positions?

I think that we sometimes believe that everybody has the same motivations because it’s easier, and they often do not. So first we need to understand what is motivating these individuals.

Some want to earn money – and compensation is an important part of talent management, but not the most important. Some might be escaping a bad boss. Others can be drawn to the prestige of the organization or its cause comes close to home. I also have seen many fundraisers become interested in a position because they like the particular geography or location of the institution and want to live west coast or in New York City or whatever.

So what might cause a top performer to consider leaving their organization for the competition?

It can be a few things. First I hear a lot along the lines of the grass always looks greener. It’s hard to know if that’s a good decision because, as I tell the individuals who bring this up, you don’t live on the other side of the fence. It’s easy to think you’ll be happier at some place that doesn’t have X or can offer you Y, without know what that actually means for the work environment. Sometimes fundraisers leave because of genuine dissatisfaction – they don’t get recognized for the value they bring, or they do not get along with supervisor, or they feel a lack of institutional commitment to development.

The best managers recognize that there’s a multitude of things that motivate people in the hiring and retention process so that they can cater their approach to the wants and needs of the individual.

Have there been any trends in front line fundraiser hiring that you have noticed over the past five years?

I’ve seen compensation levels move up fairly rapidly, especially for those who can bring in seven figure gifts consistently. In the short run this is good for the individuals benefiting from the higher salaries as well as in attracting new people to the industry. In the long run, however, I think that this puts pressure on the industry to deliver the results of this rising investment. In many places right now your average development officer makes more than star faculty members. In the long run this will produce more challenges and prompt larger conversation about value and institutional identity.

Looking to learn more? Try reading our other posts: Six Best Practices Top Development Shops Offer to Set Fundraisers Up for Success, Four qualities of strong potential development officers, and Five behaviors of top fundraisers

Mr. Flessner is a recognized expert on new wealth philanthropy and has been quoted in the New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, LA Times, Star Tribune, Dallas Star, Detroit Free Press, Chronicle of Philanthropy, Chronicle of Higher Education and many other major newspapers. He has served on the board of directors of the Council on Foundation’s New Ventures in Philanthropy. He is a frequent speaker at CASE, AFP, AHP, and other professional association conferences. His clients have included Carleton College, Concordia College, DePauw University, Gustavus Adolphus, Macalester College, Michigan State University, Oberlin College, Rollins College, University of Miami, University of Michigan, University of Saint Thomas , University of Sydney, Anne Arundel Medical Center, Arkansas Children’s Hospital, Beth-Israel Medical Center, Brown University, Children’s Hospital of Atlanta, Children’s Hospital Boston, Cleveland Clinic, Indiana University, Miami Children’s Hospital, Mississippi State University, Oklahoma State University, Phoenix Children’s Hospital, Texas Tech University, University Hospitals, University of Illinois, University of California Santa Barbara, and the University of North Carolina System. www.bwf.com